by Troy Letherman

The hallmark of fishing for rainbow trout in the Last Frontier lies in the species’ highly migratory nature—and in their reliance on the life cycle of the Pacific salmon for food. However, that very dependence on the salmon makes Alaska’s trout at least mildly predictable, even in their seasonal migrations.

Regardless, you’ll need the right fly to do it.

For Alaska’s rainbow trout anglers, who enjoy the luxury of fishing for a species that’s actually interested in eating, the task is to figure out what the prevalent food source is for the area and time of year and then to imitate that food as closely as possible. Anglers should generally choose a fly that closely mimics the size, shape, movement and color of the prey, in that order.

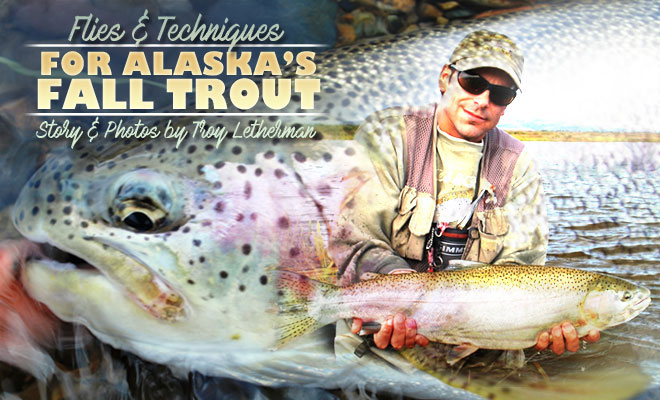

Publisher Marcus Weiner with a fine early-fall Moraine Creek rainbow.

Publisher Marcus Weiner with a fine early-fall Moraine Creek rainbow.

Trout flies are especially abundant, however, and the Alaska neophyte could easily become lost in the maze of choices. To make fly selection for fishing the state’s rainbows a tad simpler, it’s usually best to think of trout patterns as belonging to a distinct group of flies, each of which will perform better than the other possibilities under certain circumstances. Below are some of the major fly categories for Alaska’s trout fly-fishing.

First, of singular importance to the Alaska trout angler—particularly in the fall—are the rainbows’ two dietary mainstays: eggs and flesh. Glo-bugs, chenille eggs, and even beads (although not technically classified as flies) provide anglers with accurate imitations of salmon spawn, while most flesh flies, usually simple rabbit-strip creations tied in a scale of colors, can replicate the varying stages of decomposition quite well. Flesh in its early-season form (late summer and early autumn) is darker in color, often orange or a fuller pink hue. Lighter shades of pink will be more productive as the year wears on, while tans and whites gain prominence later in the fall, during the winter and again in the spring when rainbows will feed on flesh that’s washed into the stream with the higher flows. Flesh flies tied in sizes 2 to 6 on streamer-style, unweighted hooks are the most popular, though many anglers are experimenting with larger, articulated flies at present. Anglers can also use a few standard streamers to imitate salmon flesh, most notably the white Woolly Bugger and the Battle Creek. Patterns in the mold of the Babine Special that combine both flesh and egg characteristics can also be effective at times, although they’re nowhere near as widely used as the most ubiquitous Alaska trout pattern, the single egg.

The author shows off a typical western Alaska rainbow that went for a bead.

Seasonally there is a transition point when the trout really start to feed on eggs. At first when the salmon are beginning to pair up, the competition on the spawning beds makes egg fishing difficult, and fly fishers can still do well with a variety of patterns. However, as the eggs start to drop and the intense rivalry subsides, no other fly pattern will do as well. In fact, during the peak of the egg drop, the feeding is typically so intense that anglers can present an egg-imitation fly anywhere within the general area of spawning salmon and have reasonable success. It is not until the late transition from egg to flesh, when there is an abundance of eggs in the water, that the fishing becomes challenging again. Accurate imitations and flawless presentations will then regain their importance.

Autumn anglers who enjoy swinging streamers should also keep in mind the fact that sculpins, which can comprise a large portion of the trout’s diet. They range in length from three-quarters of an inch to over four inches, and their coloration will vary, often closely matching a river’s bottom. Greens, blacks, browns and combinations thereof are the most frequently used colors by fly tiers. Spun ram’s wool or deer hair is typically utilized to construct the sculpin’s most prominent feature, the large head. Some other popular and effective sculpin patterns for Alaska are the Black Marabou Muddler, the Woolhead Sculpin, the Zoo Cougar and Whitlock’s Sculpin, which is designed to swim hook-point up to eliminate hang-ups when fished directly on the bottom, where the majority of sculpins will be found.

The author took this Moraine Creek beauty on an articulated flesh pattern.

Another trout food form in Alaska waters are the freshwater eels predominantly found in the bigger lake systems. For instance, the rainbows of both the Naknek and Iliamna systems feed heavily on the eels in the late fall time periods. Articulated leeches in larger sizes, even up to ten inches, work quite well in these environs.

Without a doubt, though, many effective fly patterns really don’t imitate anything in nature. The Woolly Bugger in all its forms can loosely represent many things, but it’s meant to look nothing like any specific forage. And then there’s the Egg-sucking Leech, probably the most identifiable and productive fly across Alaska’s fly-fishing spectrum. It’s really not an accurate leech imitation, though like the Woolly Bugger, the slim profile could conceivably fool a trout into thinking it’s a minnow. The salmon-colored egg at the head certainly doesn’t hinder its effectiveness, either. In the end, the sheer adaptability of the pattern and its many triggers—profile, wiggly marabou tail, and the fact that it might look like some type of critter eating salmon spawn—makes it irresistible to a number of Alaska fish, including rainbow trout.

Mark Glassmaker with a monster Kenai rainbow in the late fall.

Photo Credit: Mark Glassmaker

When it comes to the actual fishing from late summer to early fall, most trout will be congregated below schools of spawning salmon, jockeying for prime real estate to take advantage of drifting eggs. To get in on this action, as when preparing to fish any other fly, it helps to first understand the food source. The size and color of certain eggs are very important, as not all salmon eggs are the same. An obvious example is the difference in size between smaller sockeye eggs and the larger eggs dropped by spawning kings and chums. Although the entire range of eggs may be available in the same river systems, rainbows seem to prefer sockeye eggs where large runs of those fish return. Then again, in some rivers with rather large populations of Chinook salmon, the resident trout will show a distinct preference for their eggs instead. Despite the difference in diameter, most salmon eggs are very bright orange when first dropped, and they will carry an almost translucent sheen to them. This will change, as the eggs begin to take on a milky white tint as they either decompose or begin to develop. The overall orange color will also fade through various stages of pink along the way. It pays for anglers to understand the differences, too, as the trout are certainly aware of what they’re eating.

Fish keyed-in to orange eggs will usually refuse pink or lighter colored imitations, as well as beads or egg flies that are of the incorrect size. This phenomenon is very similar to a complex hatch, where the angler must utilize all of his deductive reasoning to crack the code. The scenario can be frustrating, particularly if there are a variety of different salmon species spawning in the same river system, as the angler can fish dozens of color and size combinations before finding the right imitation. For this reason, ardent bead anglers are constantly sizing and custom blending paint to “match the hatch.”

The author brings a Kanektok River rainbow to the net during an autumn outing that was primarily geared around fishing for coho.

Beads are also difficult to fish; the technique for detecting nuances in the line requires a vigilance and skill only cultivated through thousands of hours on the water. Although the occasional village-idiot fish will always amaze anglers with its voracity, most egg bites are subtle. In fact, many go undetected. A good nymph angler can “see” the ever-so-slight hesitation in the line that signifies a pickup, but for the most part, fish will lift and reject egg imitations without the angler ever knowing they were there.

As autumn matures, days get shorter and termination dust settles atop most Alaska mountains, another change occurs as well, this one beneath the surface of the state’s many productive trout streams. On the banks and in the water of these once busy rivers the decaying remnants of thousands of salmon carcasses breathes new life into the food chain. Flesh from these rotting carcasses will provide high-calorie nutrition for insects, birds and plant life. Trout will start to feed heavily on decaying flesh and washed-out eggs as they float by. At this time of fall, the rainbows are particularly vulnerable to a well-presented flesh fly. Normal fishing will dictate that the early fly colors be oranges and reds, which resemble newer flesh. Pinks, tans, and whites should be used later in the season, as washed-out or bleached flesh is quite common when the tissue becomes thoroughly oxidized. These latter colors are normally fished from late September until freeze-up. Although flesh is readily available as a food form in late autumn, it is not unusual for rainbows to eat other parts of the salmon as well. Seeing big rainbows ingest a large pectoral fin from a decaying salmon can change one’s thinking on fly design. Using a salmon-fin fly probably borders on the sacrilegious, but having a varied assortment of trout patterns to compliment the variety of flesh flies can pay dividends during the late fall.

When fishing over spawning salmon, devising strategies tailored to the waters is paramount, as fishing the Kenai will be different from autumn angling on the Naknek and neither are anything like Moraine Creek. For example, because the Kenai River water is silty, trout there are not leader-shy. Casting over these fish and using a heavier leader will not affect anglers’ success rates. However, when fishing the very clear Brooks River, sloppy presentations will spook fish, as will heavy leaders and non-stealthy approaches. Then again, when trout are on the heavy feed, they tend to be impervious to external stimuli and will continue to feed no matter what is tossed at them. A classic example can be taken from the Kvichak River, where anglers will motor over spawning fish and then cast from a moving boat into prime lies. The fish will momentarily move away from the commotion created by the outboard, but they’ll also stay within the vicinity of the spawning fish, set to continue feeding.

Speaking of the Kvichak, potential travelers to Alaska should be aware of the sometimes-overwhelming size of some of the state’s better trophy trout locations. While many of the prolific rainbow destinations are classic freestone streams with the standard riffle-run-pool structure, many others are simply mammoth waters. Rivers like the Naknek, Kvichak, Kenai or Nushagak can be daunting and seem impossible to read. Fly fishers must break down this type of big water into more manageable quadrants and then dissect it thoroughly. Even then, covering all the prime-looking lies will be tough. For this reason, two-handed or Spey rods have become much more popular with Alaska trout anglers. Two-handed rods can be used to cast large flesh flies, sculpins, leeches and other bulky creations into zones normally reserved for all-tackle anglers. On the Naknek and Kvichak especially, anglers have combined the use of the longer, more powerful trout rods with powerboats, making quartering casts downstream from either side of the craft while anchored or under power but moving slower than the current. In this manner, immeasurably more water can be covered, which will eventually lead to more trout being caught.

Another Moraine Creek rainbow that fell victim to articulated flesh.