Written by Troy A Buzalsky photos by Troy Buzalsky and courtesy of Sea Tow Southcentral Alaska and USCG

Memorial Day was just around the corner as eager boaters patiently waited to see what the upcoming weather patterns were going to produce. As the weekend approached the forecast did not favorably accommodate, and most boaters canceled their plans of a fun-filled weekend. Whittier Harbor was almost a ghost town, but there were a few souls who decided a day on the water was better than a day at home, even with gale-force winds at 40- to 60 mph with commensurate seas at 4- to 6 feet in height.

At about 7:00 p.m. Captain Trey Hill, owner and operator of Sea Tow Southcentral Alaska received a text via a Garmin inReach Explorer satellite communicator from a “Good Samaritan” requesting assistance. The boat, a 21-foot Bayliner Trophy, had suffered engine failure and was floating perilously when the Good Samaritan provided assistance and towed them into Blackstone Bay to seek refuge and wait out the storm.

Knowing the current weather conditions, Captain Hill had concerns for the safety and security of the couple aboard the Bayliner and cautiously agreed to launch the 27-foot Boston Whaler powered with twin 300 hp outboards into the treacherous seas to render aid to one of his subscribers. Blackstone Bay is approximately 15 miles from the Whittier Harbor, but seemingly a world away in the face of a storm of this magnitude.

Once coved up in the protected waters of Blackstone Bay, the couple aboard the Bayliner managed to get the motor running and decided to head back to Whittier Harbor.

Shortly after Sea Tow launched, they received a cell-phone call screaming, “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday…” The couple in the Bayliner had broken down again and were quickly being blown toward the rocks. Captain Hill advised them to don their life jackets and anchor. They quickly admitted they had no anchor aboard their newly acquired vessel. Trey then instructed them to hail the Coast Guard, to which they replied, “On which channel?” Trey then instructed them to call out on channel 16 on their VHF radio while he was en route.

A newly acquired boat, no anchor, inadequate preparation, and stormy seas took its toll on this Bayliner Trophy and the two occupants, who narrowly survived.

When Trey arrived, he spotted the vessel washed up on a craggy beach, which in all reality was probably the best location the boat could have landed. The seas were still kicking, the winds were whipping 40+ miles an hour, with the two adults still in the boat, uninjured and clothed in T-shirts and hoodies. Sea Tow could not access the boat or the couple due to the conditions but had cellular contact with them. The couple repeatedly denied Coast Guard assistance and agreed that they would weather out the torrent gale in the vessel. Knowing he could not assist them in their current situation, Trey backtracked to the harbor with plans to return and assist as soon as the weather cooperated. Trey then updated the Coast Guard of the situation.

At one o’clock a.m. the boaters on the Bayliner called Trey back, panicking! The flood tide had arrived, and the boat had been lifted by the seas. The fiberglass vessel was being tossed around like a rag doll, crashing into waves and slamming into rocks. Trey could hear the boat literally breaking apart during their discussion. Trey jumped into action and while en route to the harbor called the Coast Guard and updated them on the situation. The Coast Guard deployed their helicopter out of Kodiak knowing the situation was dire.

Trey stayed in constant contact with the Coast Guard who stated they had lost communication with the couple and was not sure if they were still alive. They also advised that they were having a challenge with their helicopter and the weather and were delayed. Trey knows this area like the back of his hand, and he also knew the challenges and dangers they were up against.

Trey and the Coast Guard helicopter arrived simultaneously, and Trey quickly had eyes on the couple. They were out of the boat and alive with their backs against a cliff in shin-deep water with nowhere to go. The tides in Prince William Sound average about 15 feet, so what was once a safe refuge was now quickly submerging.

The two victims were hypothermic but still coherent and relatively uninjured. The Coast Guard advised Trey they could not drop a basket because of the overhanging rockery and trees, and it was too dangerous to drop rescue swimmers, so Trey, in his Boston Whaler, carefully approached the couple and made a safe pickup.

Trey’s wife Alyssa, a registered nurse, had joined him on this mission and rendered emergency care. The Coast Guard followed the Sea Tow vessel back to Whittier, where Emergency Medical Services was waiting to further care for and transport the two victims of this near-death experience.

Safety at sea cannot be understated. Unfortunately, stories just like the one Trey encountered happen all too often, and many of these can be prevented. In this column we will discuss the various elements that might just help make you a little safer the next time you hit the big blue. As Captain Hill will remind you, “It doesn’t matter how salty or experienced you are, there’s always an opportunity to learn.”

This upside-down Hewescraft required salvage services from Sea Tow Southcentral Alaska. The boat operator was traveling very fast after dark and struck a charted rock. Captain Hill explains that you should never travel faster than bump-off speed in the dark, which is roughly seven- to eight knots, max!

Redundancy

In my early fire-department days my Lieutenant used to always say, “If one’s good… two’s better.” I’m pretty sure he was talking about snacking on cookies, but in the off-shore boating world redundancy is king, because “Murphy” always seems to enjoy a boat ride. I can’t count how many stories I’ve heard when it comes to a failed VHF radio, losing a motor, a GPS crashing, or a bilge failing when it’s needed most. In most of these cases a portable VHF radio, kicker motor, compass, or hand-held bilge pump could make the difference between a real on-the-water emergency, or just a mild inconvenience. Remember, your invisible co-pilot, Murphy, believes “If anything can go wrong, it will,” typically in the worst place, at the worst time, and when you are least prepared.

Plan For Disaster

Acronyms are a great way to remember a phase, and “Plan For Disaster” has a simple acronym—PFD—which also stands for personal floatation device. Most boats and boaters have PFDs on their boats, but the question is, are they worn at all times? A seatbelt is worthless if it’s not worn in a crash…same with a bike helmet. So, the rhetorical question is, “What good is that life jacket if it’s not on the boater at the time of the incident?”

Not so many years ago a tragedy unfolded off Oregon’s Columbia River bar. In a nutshell, a jetboat was just outside the jetty when a wave filled the boat’s bow, lifting the jet pump out of the water. Before the boat captain could react, another wave crashed, half filling the boat. In a melee of panic, one occupant attempted to don his inflatable PFD, when yet another wave crashed over the gunnel, filling the boat and forcing the crew to abandon ship. The gentleman’s inflatable PFD activated, but because of the hasty donning, the harness straps wrapped around his neck, and he ultimately was strangled by the very tool meant to save his life. Tragically, this is just one reason why inflatable PFDs should be be worn at all times.

Not all PFDs are identical, being engineered for specific water conditions, specialized applications, and with differing buoyancy ratings. Choose a PFD that fits your application and your body.

Abandon Ship…or Not

When the brown, smelly material hits the fan in a big way, the captain and crew may have to make the life-or-death decision to either abandon ship or ride it out (go down with the ship). Abandoning the ship needs to take place at the right time, followed by specific steps and procedures, as the decision to leave the vessel and enter the sea comes with great risk. Abandonment of a vessel should only occur after the crew has done everything possible to prevent the danger and to ensure the safety of everyone onboard. Examples might include an onboard fire, taking on water, capsizing, or a collision.

Sometimes the abandon-ship decision builds slowly, allowing the crew and passengers to methodically prepare. Other times the situation unfolds quickly, and as we all can appreciate, when decisions unfold quickly mistakes often occur. We’ve all participated in fire drills to one extent or another. Others have participated in marine mustering drills, assembling at accountability points where you’ll board your life rafts. But how many folks reading this column have ever had an abandon-ship drill or discussion? You know what they say…Proper planning prevents poor performance, and “winging it” is not a plan.

More than one boater has abandoned ship only to make the situation worse. A disabled boat alone is not a reason to abandon ship, but it might be a great reason to drop anchor. A sinking or partially submerged boat also might be safer than the abandon-ship option, to a point. Life rafts are great and can be part of your planning-for-disaster gameplan but consider that you will have fewer resources once you’ve abandoned your master vessel and board the life raft. You will be more difficult to spot. If you are confident that you and your crew are in danger if you remain onboard, it’s time to leave.

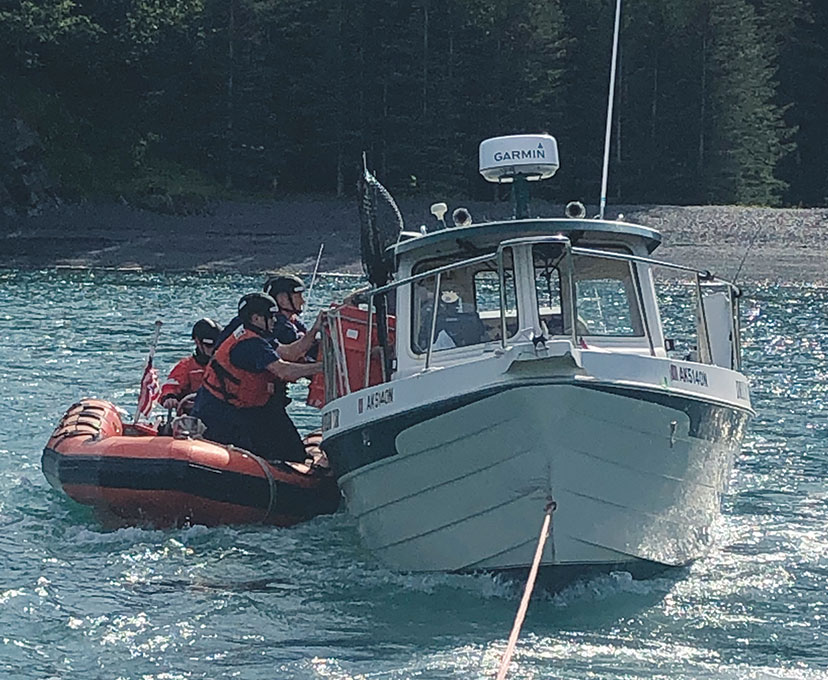

Sea Tow and the USCG assisted this vessel out of Resurrection Bay to safety after it took on water from a hole in the seawater intake. Sea Tow provides towing services for mechanical failures and vessel damage, salvage operations, fuel drops, and jump starts. This boat assist required a team effort of the USCG and Sea Tow including moving all occupants into the Sea Tow boat for their ride home.

Mayday Mayday Mayday

Originally from the French term venez m’aider meaning “come help me,” the word Mayday is used to signal life-threatening distress. When used in sequence, Mayday, Mayday, Mayday are three words that will bring a lump in one’s throat when you hear it on your marine radio.

Throughout my career as a firefighter, we drilled once a month on Mayday procedures, knowing that if we ever needed to issue a Mayday it was already too late to practice or brush up on our communication skills. My Dad always said, “The fire gives the test before the lesson,” and this thought process can be similarly applied to on-the-water emergencies where the boat sinking or capsizing is giving the test before the lesson.

This vessel was set onto the rocks after a crab-pot line fouled the propeller. All five persons on board were able to leap onto the jetty safely and await assistance. The Coast Guard reminds all mariners to remain vigilant in wearing life jackets, having an anchor onboard, keeping a sharp lookout for hazards to navigation, and the possibility of rapidly changing conditions.

Practicing a Mayday transmission should be a regular part of every boat-captain’s routine. Let’s go over the key elements of a Mayday message. First off, make sure you are on the correct radio channel, in this case, channel 16 on your VHF radio. If there is a Digital Select Calling (DSC) button, push it and it will transmit your GPS location if installed and hooked up correctly. This is also a good time to consider activating an emergency position-indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) or Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) if available.

Staying calm (easier said than done), transmit “Mayday” three times: “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday.” Then state your name, location, and number of people on board. Do not take up unnecessary airtime with garble; the first priority is being heard. Once the Coast Guard replies be ready to fill in the essential information, which will include the boat’s name, the nature of the problem, type of assistance needed, condition of the boat, injuries or fatalities, description of the vessel, and the emergency and survival equipment.

A Mayday example might sound like this: “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday, this is Troy Buzalsky on the Fishing Machine. We are located approximately ½-mile west of the Columbia River south jetty and drifting to shore with four (4) passengers onboard. Break.”

Now wait for the Coast Guard to reply. They will acknowledge your Mayday and request additional information. Listen carefully and follow any instructions offered and answer all questions. This is not the time to be elusive, or to try to shelter yourself from fault or blame. VHF radios do have limitations, including transmission range based on line-of-sight, but consider other vessels in your immediate area as also potential forms of assistance.

A life raft is a great safety tool when navigating offshore. When that ominous order to abandon ship is declared, you’ll be glad you have a life raft aboard.

First Aid

First aid on the big blue can range from treating simple sea sickness, to a twisted ankle, an impaled fishhook, or a host of other onboard injuries. It could also include medical emergencies like a heart attack, stroke, diabetic emergency, seizure, cardiac arrest, or a myriad of other possibilities.

Time matters in a true medical emergency as your brain will start to die after four- to six minutes without effective circulation. In a cardiac arrest (pulseless and breathless) the body has no effective circulation, whereas in other medical emergencies, the circulation may be compromised but present. In these cases, the best hope for a positive outcome is timely, definitive medical treatment, and in most cases, this cannot be achieved on your typical sport boat so rapid transport is the best option.

Being trained in first aid is a good first step and having a well thought out first-aid kit can also make a difference. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has gone through many changes since I became a paramedic in the early ‘80s, and today’s high-performance CPR focuses more on compressions than ventilation, which makes it more acceptable when performing on strangers. Bottom line, learn CPR, because whether you’re on the water, or on land, the most likely situation in which you’ll have to do CPR is to a family member.

Knowing your waters and the surrounding hazards is an important part of a safe day on the water. Weather, wind, waves, the tide, and onboard distractions can quickly change, and an alert captain must read and react to each situation.

Wind, Wave and Weather or Not

Weather is the state of the earth’s atmosphere with respect to temperature, humidity, precipitation, visibility, cloudiness, and other factors. All weather can be traced to the effect of the sun on the earth. Most changes in weather involve large-scale horizontal motion of air. Air in motion is wind, and wind can be a boater’s arch enemy.

There is a direct relationship between the speed of the wind and the conditions of the ocean. The formation of waves, white caps, and sea spray depend on three factors: wind speed, duration, and fetch (sea area). The higher the wind speed, the longer the wind blows, and the greater the fetch translates to the greater the sea disturbance, which includes wave height, wave length, wave crest, wave trough, wave period and frequency.

Leaving Whittier on an 80-mile offshore journey, the seas are calm, but knowing the weather forecast can help make the decision to go…or not go.

Wind waves are waves produced by the local prevailing wind. Swell waves are waves that have moved well away from the area where they were generated and have settled into a regular traveling pattern. Before your trip, carefully examine the ocean conditions, including wave height, wind waves, and wave period (time between waves). As a general rule, you want your wave height as small as possible, you want your wind waves even smaller, and you want your wave period to be preferably larger than the combined total of the previous.

It’s one thing to be concerned about the weather so you can be dressed appropriately. The scary fact is, weather can create deadly circumstances for the ocean-going boater, and it cannot be stressed enough how important the weather forecast can be both for your trip’s enjoyment, but more importantly, its safety. When you accept the responsibility to take your boat offshore it should be with the knowledge of current and forecasted weather, and how that may influence your trip. Captain Trey Hill recommends looking at weather from at least two sources, like the Windy live wind app and the NOAA Marine Forecast and Weather app. I have also had excellent results using my Garmin inReach weather-forecast function.

There is a direct relationship between the speed of the wind and the condition of the ocean. The formation of waves, white caps, and sea spray depends on three factors: wind speed, duration, and fetch. These anglers are enjoying a slow swell while filling the fish box.

Your Anchor—Your Friend

A common question when making plans to take your recreational boat inshore or offshore is, “Why do I need to take my anchor? I’m not going to anchor up or anchor fish.” The mindset is, let’s leave it behind. We don’t need the added weight, we don’t need it banging around, and the saltwater won’t do it any favors.

Even though you can pretty much talk yourself out of taking your anchor (I have), Recreational Boating Safety Specialist Dan Shipman of the United States Coast Guard offers this simple safety reason why an anchor is a good idea. “Let’s say you are going out and there is some wind and/or current. Your engine breaks down and you are drifting into the surf or onto the rocks. The anchor will help keep you in safe water.” So, there you have it. Make sure your anchor makes the trip every time you venture out.

Sea Tow’s Trey Hill has seen several incidents where boaters had an anchor on board, but never gave it a second thought as a safety tool. As he illustrated in the earlier story, the Bayliner didn’t have an anchor. Hill has also encountered boats with hydraulic-over-electric winches that either didn’t have an emergency drop feature, or the user didn’t know how to activate it without power. Knowing your vessel and its essential equipment is crucial.

Having a Plan

This rental boat had a mechanical failure approximately 60 miles from the Whittier Harbor and was safely towed home by Sea Tow Southcentral Alaska for repairs.

I have always said that if your house is on fire you need to have a plan and jumping out a window is not a plan…It’s a reaction to not having a plan. When boating, you also should have a plan, which might include a float plan to let your spouse, family, friends, or loved ones know where you are traveling and when you plan to return. There are many examples of float plans online, but for me the most important elements are where you are going, when will you return, who is with you, and how someone can get a hold of you.

Towing a boat can be dangerous for the untrained Good Samaritan rescuer. Sea Tow boats are carefully designed for safe towing, and Sea Tow operators require boat handling skills and must be licensed as a USCG Captain with Tow endorsement. Sea Tow Southcentral Alaska covers the waters surrounding Whittier, Seward, Valdez, and Homer.

In my old jet-boating days we used to keep a list of names of our friends and jet-boat enthusiasts that all agreed to make themselves available should we put our boat upon some rocks or need on-the-water assistance. Having a friend network is great, but when venturing offshore it’s hard to beat having a Sea Tow membership that covers the waters in which you will be traveling. Sea Tow offers peace of mind 24/7, 365 days a year to assist you whether you have a major breakdown, need a tow, or perhaps just a jumpstart or a fuel drop. I have seen Sea Tow in action and would not own an offshore boat without a membership. For more information go to: seatow.com/southcentralak.