Trawl fishing is one of the major contributing factors to wanton waste in the fishing industry. Every angler, whether sportfishing, subsistence or commercial fishing has a responsibility to shoulder their share of the burden of conservation when it comes to protecting Alaska’s fisheries.

When people think of fishing in Alaska, they conjure up visions of big and plentiful when it comes to the variety of species available to catch. While there are still some fisheries in the Great Land that are amazing, many salty ol’ captains reminisce about the old days of big and plentiful and whatever fish species you want to talk about. Some of the yarns should be treated like any fish story, but there seems to be a common thread in that certain species of iconic Alaskan fish species are definitely not as big or abundant as they were two or three decades ago. There is data out there to support these claims of lower abundance and size. The real issue is nobody can agree on what is causing these declines, and as we find answers there seem to be more questions that pop up.

Struggling Fisheries

Halibut over 100 pounds don’t seem to be as common as they were 20 years ago. A range of factors are at play, but we can control how we manage them to allow more big breeders to spawn. © Scott Harris

It isn’t hard to find recent articles or reports in mainstream Alaskan media talking about the severely struggling Chinook (king) salmon runs throughout the state. Outside of Alaska there is minimal press about the issue. There’s also the fact that residents on the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers haven’t been able to subsistence fish for kings and chums for multiple years. What isn’t even discussed anymore is how there hasn’t been a consistent in-river harvest opportunity on wild kings in Cook Inlet streams or on Kodiak Island streams in a decade or more. If it was an in-river habitat issue there would be localized runs that would be struggling, but since it is across the board where we see these significant declines, then it must be something happening to our state fish (Chinook salmon) while they are spending two- to six years in the saltwater.

Anytime there are declines in Mother Nature, there is rarely one smoking gun. There are almost always multiple factors that go into a declining population. Many of those factors are outside of human control. No matter where you stand on the climate-change issue, you would have to be living in a cave to not see that we are seeing changes in our climate. It is a natural process that has swung back and forth since the dawn of time, and this can adversely affect species that live in a narrow environmental niche. The aforementioned king and chum salmon declines as well as the devastating collapse of crab populations in the southern Bering Sea have all been blamed on climate change. Is it the sole factor in their declines? No, but I’m sure it isn’t helping their populations stabilize and sustain the current level of human interaction.

The Conservation Burden

As humans, we don’t have much control over what the climate cycles do or don’t do, but we can totally have control over our interactions with various species. Any angler can see changes to our retention limits anytime there is a change in abundance in any of the species we target, whether up or down. Unfortunately, sport anglers and subsistence users get the short end of the stick nowadays when populations of various species are in decline. The conservation burden feels like it always falls on the shoulders of sportsmen anytime a species is in decline. Even though anglers contribute large sums of money per pound of fish they harvest to the state economy, our political contributions seem to fall short of making sure we get a fair piece of the pie.

Isn’t management of fish just science and math? In a perfect world it would be, but there are many different user groups for each species of fish and each one has their own unique impact on the population. You have sport anglers, subsistence, directed commercial harvest, and commercial bycatch that all must be accounted for. These are managed in Alaska by both the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) as well as the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council (NPFMC). There is significant crossover in how various fisheries are managed, though, and who has primary oversight.

Management and User Groups

Anybody who has fished in Alaska is familiar with ADF&G, but most aren’t aware of the NPFMC. The NPFMC is one of multiple regional fisheries councils established by the Magnuson-Stevenson Act of 1972. Ideally, having regional fisheries management was to have regional stakeholders involved in the process to make sure nobody was left out when allocating catch among user groups. A sound concept, but greed and human nature has put overall long-term, sustainable health of certain species at risk to maximize economic value of other species. Currently there is noise in Congress to change some wording in the Magnuson-Stevenson Act to prioritize sustainability over economic value, which should be a huge win for recreational and subsistence users as well as the fish.

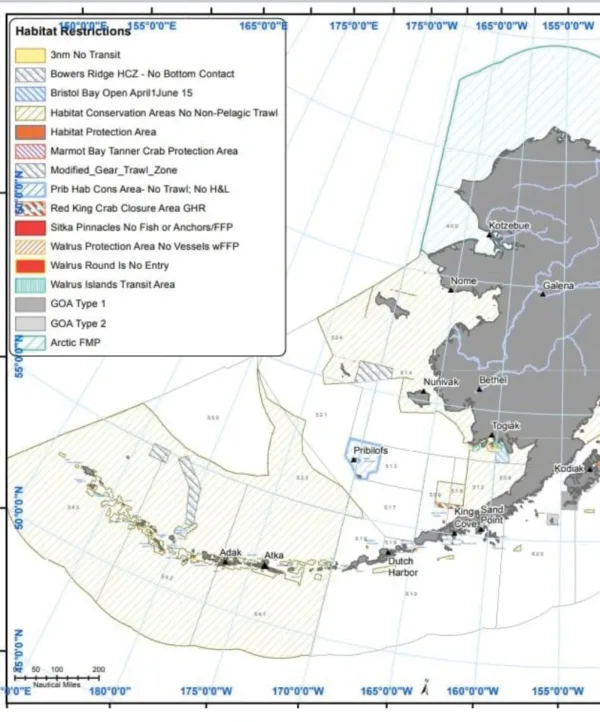

Habitat restrictions in the Bering Sea with most restrictions tied to trawl gear. Areas with no nonpelagic trawl like Norton Sound still have viable crab fisheries. © NOAA Fisheries

Now that the governing bodies have been identified, who are the user groups that are involved in various fisheries that target the same beloved species that us recreational fishers are enamored with? Outside of recreational and subsistence use you have commercial fisheries that take the vast majority of available harvest for a particular species. There is nothing wrong with utilizing a directed commercial harvest on a fish species that contributes both to the livelihoods of fishing families and provides tax revenue for the state—as long as it is managed sustainably. The issue lies where certain fisheries and gear types are leveraging themselves to get more than everyone else. This is when the failure of the Magnuson-Stevenson Act is most evident. When a user group has a higher bycatch than the directed fisheries, it is a pretty good indicator that the governing process is failing.

Bycatch Mortality

All fishing has a certain level of bycatch, which is when you catch non-targeted species. So, anytime you catch a Dolly Varden while targeting rainbows, or a pink while targeting silvers, it is bycatch. The same concept applies in any commercial fishery. They have bycatch, but on a much larger scale. It is just a part of fishing, no matter what tactics you employ. The biggest thing is mortality and how much is acceptable for that particular species.

Mortality levels are drastically different depending on what gear you are using. A hook-and-line-caught fish is going to have a relatively low mortality rate (example: Kenai kings caught-and-released on sport tackle show a mortality rate of roughly 6%) while something sitting at the cod end of a trawl net with tons of fish pushing down on it for an hour while being towed at five knots isn’t going to survive. Period. By and large, commercial bycatch is dumped overboard. Wasted.

Mortality of any fish species, whether directed fisheries or unintended bycatch, should be managed based on abundance. Fish populations are a very dynamic, constantly fluctuating number that are affected by a multitude of variables. Many of those variables are outside of human influence and control, but the one we can control is mortality on a particular species in the various fisheries that come into contact with them. Wouldn’t it make sense to keep that mortality in a percentage range that allows the fish populations to be sustainable even when there are declines in the population? It totally does, as that is how plenty of successful fisheries have been managed for years! But what happens when a fishery goes outside of that sustainable catch (or bycatch) number? They should be shut down, whether it is a directed fishery or indirect bycatch.

Chinook Salmon Trawl Fishing Bycatch

Let’s look at Chinook salmon bycatch in the Gulf of Alaska commercial pollock fisheries, which is dominated by pelagic trawl gear (trawling nets that are meant to be dragged mid-water column). This fishery has 100% monitoring whether by electronic means, or a NOAA-certified individual that collects data on what is caught. The data they collect is then used to extrapolate various indices like age, growth rate and sex ratio for both the targeted species as well as on prohibited species like Chinook salmon or halibut.

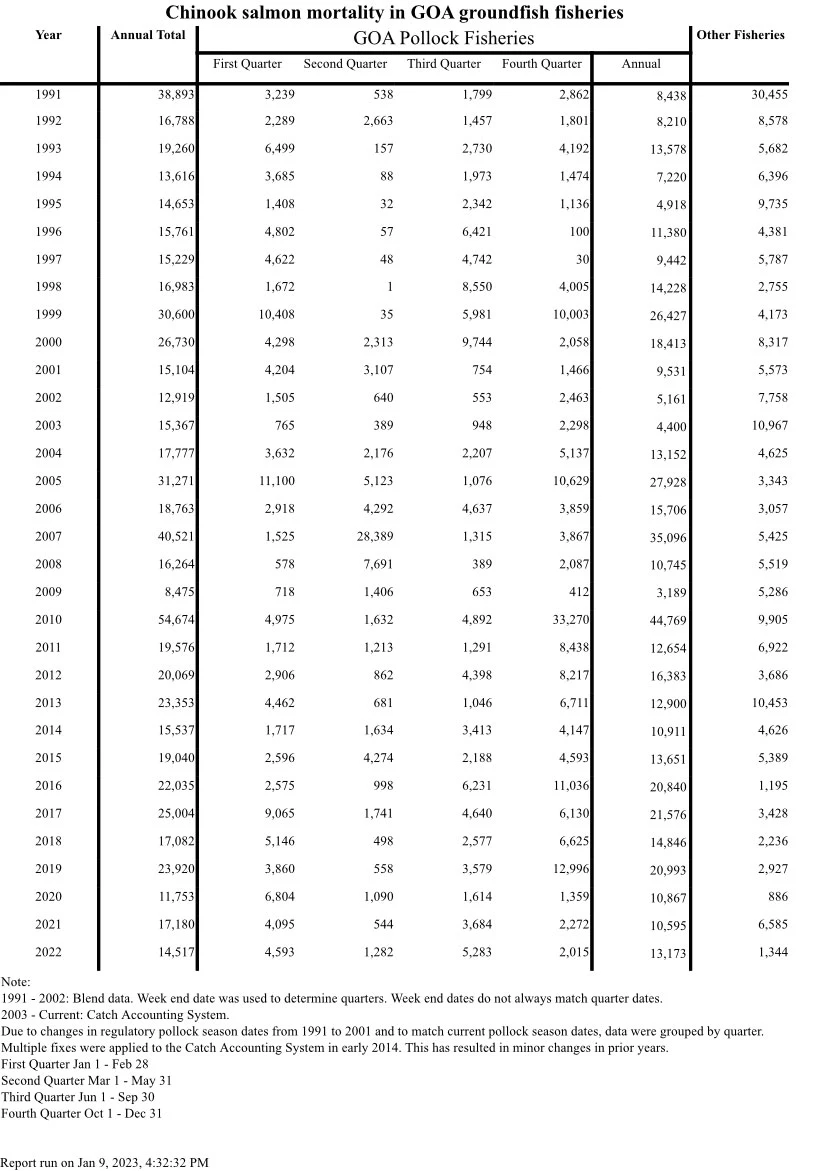

Looking through data going back 20 years, there is a correlation between bycatch numbers and declines in Chinook returns to rivers in southcentral Alaska. A great example is prior to 2004 there were usually about 15,000 or less Chinook that were reported as bycatch in the Gulf of Alaska trawl fisheries. Since then, 8 of the past 18 years (data through 2022) more than 20,000 individual Chinook were reportedly caught in trawl nets. A couple of notable years with significant Chinook bycatch were 2005 (31,271), 2007 (40,521), and 2010 (54,674) (source). That doesn’t seem like very many until you look at historical escapement data of Chinook through either weirs or sonar stations in southcentral Alaska rivers.

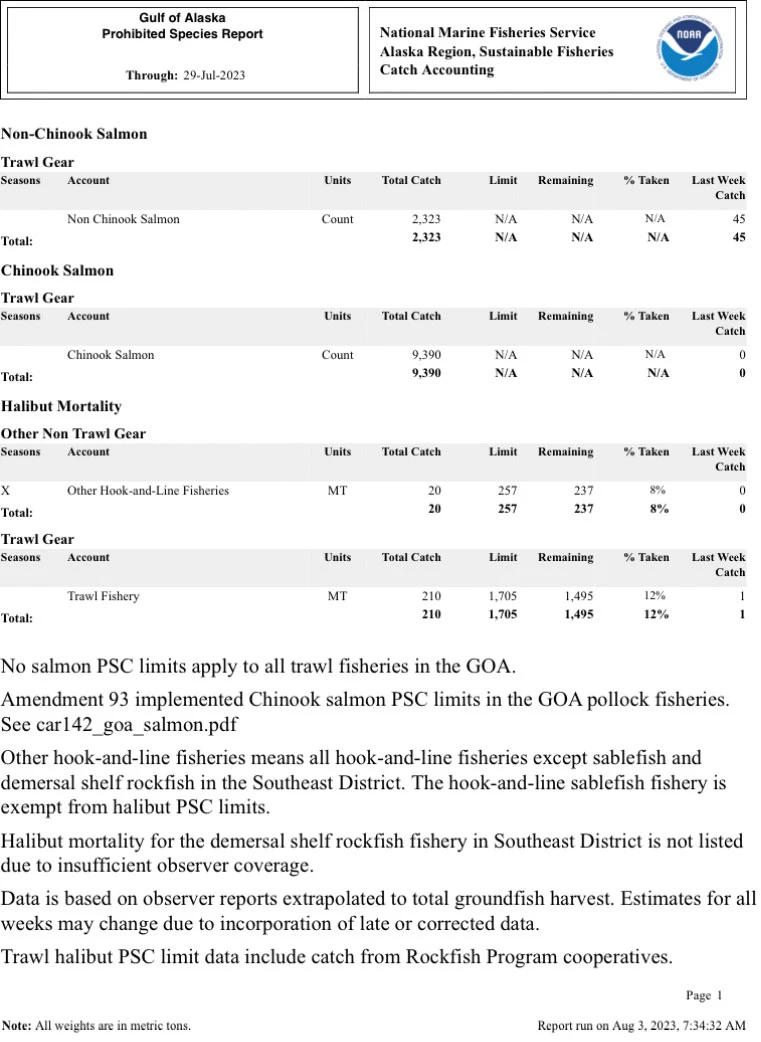

Gulf of Alaska prohibited species catch for the year as of July 29, 2023 showing salmon and halibut bycatch in the trawl fisheries. Over 9,000 individual Chinook are estimated to have been caught as bycatch, while many rivers in southcentral Alaska have some of the lowest escapement numbers on record. © NOAA Fisheries

Trawl Fishing Impact

Chinook salmon are the least abundant of all the salmon species with most smaller rivers in southcentral Alaska having escapement numbers well under 10,000 fish for the past 18 years, with only a few getting above minimum escapement some of those years. Rivers like the Karluk or the Ayakulik on Kodiak Island and Chignik on the Alaska Peninsula have a minimum escapement goal of 3,000, 4,800 and 1,300 respectively. Even big rivers like Deshka have a minimum escapement goal of just 9,000 fish. The Kenai has a combined minimum Optimum Escapement Goal for early and late runs of 18,900 (source). What is the cumulative effect of taking that percentage of a species out of the gene pool? Can populations that have a genetic bottleneck adapt to changes in their environment as readily?

The other question is: Where do the Cook Inlet and Kodiak Island kings go to fatten up for a few years before returning? They definitely have to out-migrate and return through the Shelikof Strait, where there is an intensive trawl fishery for pollock in winter through spring, but some trawl fishing continues the rest of the year as well.

Gulf of Alaska Chinook mortality from 1991-2022 in groundfish fisheries. The pollock fishery denotes pelagic trawl while other fisheries numbers cover nonpelagic trawl as well as hook-and-line (longline or jig) and pot fisheries. © NOAA Fisheries

Is it out in the Aleutian Islands or further where they also have to contend with international fleets deploying trawl or drift nets, catching anything and everything? What about the salmon in western Alaska that are from the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers? They definitely have to spend a portion of their lives traveling through the gauntlet of trawl nets in the Bristol Bay region to get to or from their natal streams. Maybe adjusting season timing would be a prudent option to minimize impacts.

Alaska Crabbing Waste

Discard of dead crab caught as bycatch. © Alexus Kwachka

Something that is also quintessential in Alaska is crabbing. Thanks to the hit TV show Deadliest Catch, outsiders and sourdoughs alike are enamored by the romance of making a big payday on the crab grounds of the Bering Sea. Unfortunately, those days might be long gone or severely restricted going forward. The Bristol Bay red king crab season and Bering Sea opilio crab seasons were shut down last year due to the disappearance of millions of crabs (but it sounds like they will get to fish this season). The convenient scapegoat for this precipitous decline is, of course, climate change causing sea temperatures to rise. There are some other possibilities to consider, since a crash like that isn’t caused in a matter of months by slowly rising sea temperatures in the southern Bering Sea.

Trawl Fishing Pressure on Populations

Further north in the Bering Sea, the Norton Sound red king crab population seems to be doing just fine to support a limited commercial fishery. To the south, in the Gulf of Alaska, the Kodiak Island tanner crab fishery was phenomenal this past season which wasn’t too far from the epicenter of the warm water “blob” that plagued the northern Gulf of Alaska from 2016 through 2019. Tanner crabs take five years to reach maturity, so if warm water causes crabs to die off at unprecedented levels, then the Kodiak fishery shouldn’t have been good for another two to three years.

So, why would these crab fisheries be stable or booming when others not that far away have crashed? The convenient answer is that Mother Nature creates beautiful coincidences. It could also be because of lack of nonpelagic trawl pressure. There is a prohibition on nonpelagic trawling in Norton Sound, and around Kodiak the nonpelagic trawl fishery for yellowfin sole and arrowtooth flounder hasn’t been worth the effort due to poor prices thanks to increased tariffs with China.

A dump truck full of Pacific ocean perch driving down the road in Kodiak. © Alexus Kwachka

What motivates overconsumption?

We must ask ourselves, how did we get to this point? Human nature, I guess, as this is a story that has been told multiple times throughout history. The greed of having to have the most of whatever resource, whether it’s fish or timber or minerals, is a fact of life. Greed clouds the human ability to think about the long-term future because you think you have to have it all right now.

Another question we must ask ourselves is what happens when it all crashes down? Private equity firms that own big fishing operations can sell their assets for a nice check and retire comfortably. What about the small operations that live off a much smaller margin and who have invested everything they have into something they love? There will be some tax-funded bailout money provided to the losers for a short time, but at the end of the day the fish will still be gone, along with people’s way of life that sometimes spans generations.

Practice Resource Management

Waste isn’t just a problem in commercial fishing. Something to think about as recreational anglers and even subsistence users is we need to look at ourselves, too. How much do we really need to sustain ourselves through the year when it comes to fish or game in our freezers? How much of what we harvest in our recreational, personal use, or subsistence fisheries gets wasted? There is a mentality that because the law says this is the bag limit, it has to be caught at all costs, otherwise it wasn’t a successful trip.

For years I have watched as people come to Alaska to go sportfishing and hundreds of pounds of fillets go back with them on the plane. How much of that did they actually finish eating before it was freezer burnt and thrown out? Why can’t the value of the fishing trip be based on the unique experiences and things seen instead of the poundage brought back home? In the end, every user group needs to look at their own practices and make sure we are doing the best we can to respect and conserve our resources so that future generations can experience the joy of fishing.

Josh Leach can be found in the waters near Larsen Bay on Kodiak Island during the summer months. The rest of the year sightings of him generally occur in or near the rivers, frozen lakes and breweries of southcentral Alaska.

Trawl fishing is a major current issue in the fishing and outdoor world. For more reading about Alaska fisheries check out Fish Alaska’s article archive.