Restoring Cook Inlet Chinooks

Story by Marian Giannulis

If you are fishing in Alaska with the hope of catching the official state fish—the Chinook, or king salmon—there’s a chance you will wet your line in the southcentral region of the state. Southcentral Alaska has historically accounted for 60% of the state’s Chinook salmon sportfish harvest and with good reason. The region’s mighty Susitna River is the fourth-largest king salmon run in Alaska. The famed Kenai River still holds the world record for the largest sport-caught king at a whopping 97 pounds, 4 ounces. The region boasts plentiful and world-renowned fishing opportunities, it’s the location of the state’s major population and travel hub, and it is accessible on the road system, unlike many other places in Alaska.

Josh Williams with a Cook Inlet Chinook. © Austin Williams.

These factors might have you planning your next fishing trip in southcentral Alaska, but unfortunately the reality of king fishing here today isn’t all strong runs and tight lines. King runs across Alaska have been in decline, and Southcentral’s Kenai Peninsula and Matanuska-Susitna Borough fisheries are not immune to that trend. As of January 2022, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) had already released four emergency orders restricting wild king salmon fishing to catch-and-release only in the Matanuska-Susitna Borough and on the Kenai Peninsula. Catch-and-release is a great way to still enjoy fishing for kings, but when these fisheries once supported harvest and no longer have the numbers to do so, it is cause for concern.

Biologists have been studying the decline of king salmon for over a decade, but rather than pointing to a single cause, their results instead list many contributing factors: warming oceans and rivers, overfishing, loss of habitat, and more. There’s no denying that sustaining king salmon runs for future generations will take a holistic approach that addresses all contributing factors, and that this issue needs to be addressed soon, before it’s too late. Alaska has the opportunity to address a significant factor right now: maintaining the rivers where kings return home to spawn and where juvenile fish begin their lives.

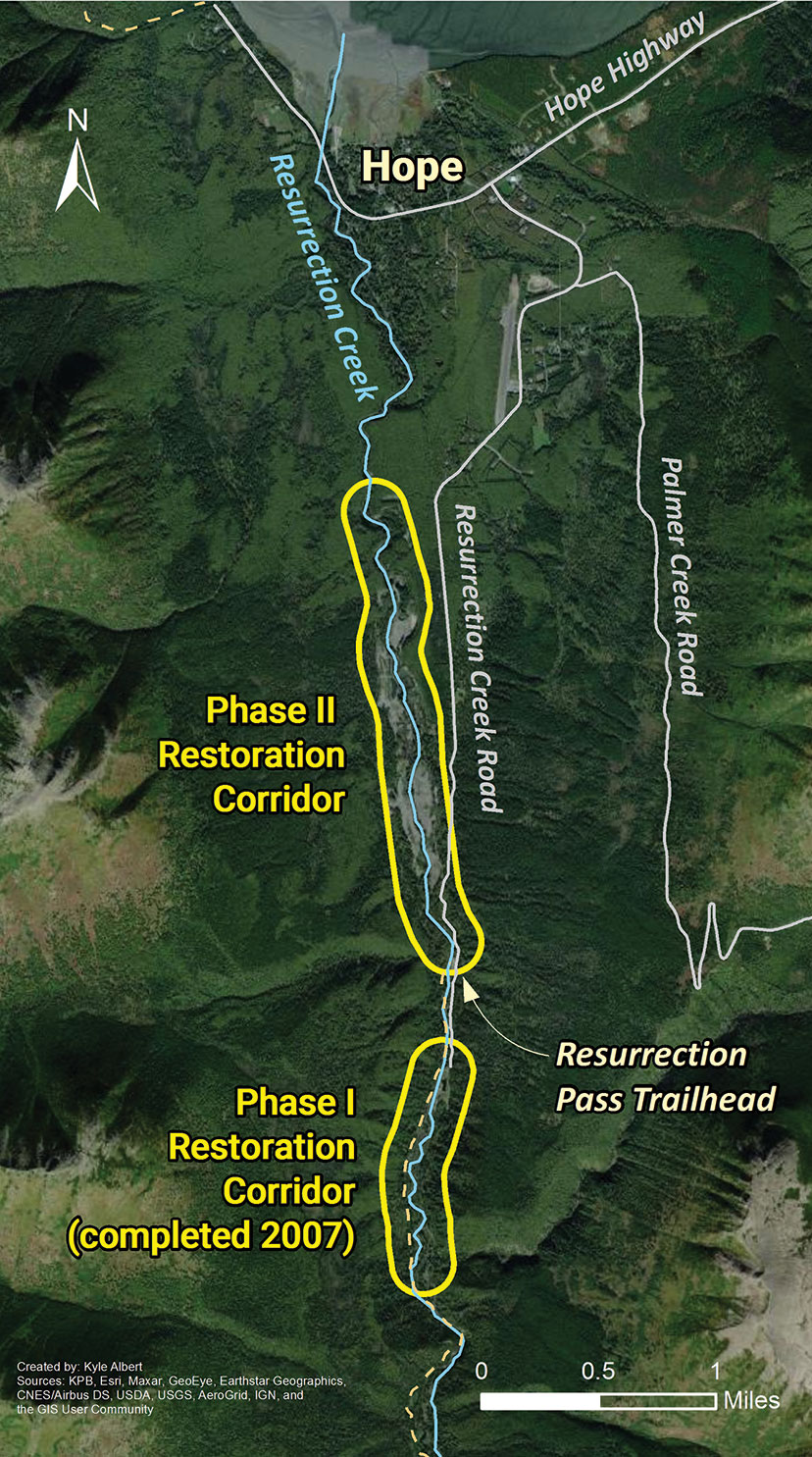

The restoration areas of Resurrection Creek. Map by Kyle Albert.

Salmon are strongly influenced by environmental conditions in the rivers and streams where they spawn and rear. We must maintain their access to these environments and conserve conditions within them to sustain healthy populations of these fish. There have been significant efforts to do so throughout the Kenai Peninsula and Matanuska-Susitna Valley, where population growth and development have often occurred right alongside salmon streams. These efforts include riparian protection zones along the banks of rivers, bank closures to protect spawning and rearing habitat, and light-penetrating walkways that allow necessary vegetation to grow underneath. It also includes the replacement of bad culverts that block fish passage to spawning and rearing habitat, and the construction of new culverts to standards that allow for fish passage.

Restoring degraded rivers is another key way to support healthy spawning and rearing grounds for king salmon. We have a great example of that happening in southcentral Alaska right now. Resurrection Creek flows out of the western Kenai Mountains into Turnagain Arm through the community of Hope. The lower six miles of creek provide critical spawning and rearing habitat for king, silver, chum, and pink salmon. It is one of a few streams of its size and type in upper Cook Inlet that supports king salmon.

Resurrection Creek was the site of one of Alaska’s first gold rushes. Historical placer mining in the early 20th century left the stream a far cry from its natural state, straightening the river channel, removing important salmon spawning gravel, and significantly reducing slower-water areas that are critical for young salmon survival. This habitat loss decimated the stream’s once-thriving salmon runs.

Installed logs and rootwads within Phase I of Resurrection Creek’s restoration area. © Marian Giannulis.

In 2002, the U.S. Forest Service collaborated with the Enterprise Watershed Restoration Service to begin restoring a 1.5-mile section of Resurrection Creek. This effort, which became known as Phase I of the Resurrection Creek restoration project, reconnected the historic floodplain, stream channels and riparian areas; constructed new pools, side channels and ponds; installed logs and rootwads in new stream channels; and revegetated the riparian areas. Following the completion of Phase I, fish and wildlife immediately responded. In 2007, just one year after restoration was completed, the observed numbers of adult king salmon increased six-fold, and the population has continued to increase.

The success of Phase I showed that additional restoration would likely have similar benefits along other sections of Resurrection Creek, and the Forest Service began planning Phase II for a 2.2-mile segment in the lower and more accessible stretch of the creek. Phase II eventually stalled due to a lack of funding, but a unique partnership between the Forest Service, Trout Unlimited, Kinross Alaska, the National Forest Foundation and Hope Mining Company brought together the funding and access necessary to complete the project. Phase II of the restoration project will begin in earnest this summer.

This partnership is the first of its kind in Alaska. The collaboration of a federal agency with mining companies and conservation organizations speaks to the importance of this work to all. Alaskans and visitors alike have a vested interest in sustaining the salmon runs that bring life into the state. If we are to ensure that our faltering king salmon populations have a future, it will take more collaboration like this and prioritization of the habitat they need to survive. The restoration of Resurrection Creek is one piece in a vast puzzle, but when we are talking about the future of the king of fish, every piece counts.

A damaged riparian area within Phase II of Resurrection Creek’s restoration area. © Marian Giannulis.

Across the western coast of the contiguous United States, king salmon populations are a fraction of their historical size. Many runs have completely disappeared, while two current west coast king populations are listed as endangered and seven more are listed as threatened. Fortunately, there are currently no Alaska king salmon populations listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Alaska has the opportunity and ability to get the salmon story right. The life cycle of king salmon begins and ends with freshwater habitat. Let’s make sure our effort to sustain these populations recognizes that. Every time you see fencing blocking travel over streamside vegetation, an old culvert being replaced, or a major restoration project like Resurrection Creek, know that each effort is contributing a crucial piece to the survival of salmon.

Trout Unlimited’s mission is to protect, reconnect and restore North America’s coldwater fisheries and their watersheds. Learn about our work in Alaska at w.tu.org/tu-programs/alaska. Marian Giannulis is the Alaska Communications & Engagement Director for Trout Unlimited.